Ettore Sottsass is not as mid as I thought

A personal essay on Barneys New York, MoMA's 1972 exhibition "Italy: The New Domestic Landscape", and trusting moments of serendipity in the age of Main Character Syndrome

In the summer of 2021 I was brought onto a bold and ultimately ill-timed arts and culture project at the former Barneys New York flagship on Madison Avenue. We were the first tenants to take over the building after the famed department store had declared bankruptcy in late 2019 and subsequently closed in February 2020, followed by over a year of vacancy as the pandemic similarly shuttered the city the following month.

Entering the revolving doors of 660 Madison for the first time that August resembled what I imagine it must feel like to step onto a cultural site before an archaeological survey. There was the felt sense that something important had happened here, and that something cataclysmic had collided with this “something important”, resulting in the debris splayed across the gray marble floor that we were now gingerly stepping around. The post-apocalyptic “new normal” that the world anxiously anticipated during the first few weeks of the pandemic had actually befallen Barneys: There was no power nor AC. Every floor was infested with cockroaches and trashed with retail supplies and displays that, through the passage of time and their new context, had become contemporary artifacts.1 Faucets sputtered brown water. Empty clothing racks were toppled over as if retail associates had to make their exits in haste. There was a Ouija board stuffed behind a register on the third floor. The upholstered banquettes in Fred’s smelled of the rotten eggs and meat that had spoiled in the kitchen’s industrial freezer. Notepads on desks in the ninth floor executive offices had last year’s to-do lists still to be crossed off, left next to stained coffee mugs that never made it to the communal kitchen sink.

In search of a place to work and altered by the vestiges of chaos around us, my colleagues and I began pillaging the aforementioned offices of former executive employees. I took over a room at the end of the hallway because it had a window, a sliver overlooking 60th Street. This was my first time in an office environment since the pandemic, and while it was new it certainly did not feel normal. The room was adorned with personal effects as if it still belonged to someone. I flipped through an abandoned Rolodex on a shelf above the desk—a carousel of handwritten beeper numbers, business cards from the city’s top plastic surgeons and dermatologists, Michael Jackson’s long-expired Barneys New York credit card number, and a wealth of personal information from other celebrities, designers, and brands dominating the early 00s zeitgeist—and gleaned that this office had once belonged to a higher up within the store’s beauty department.

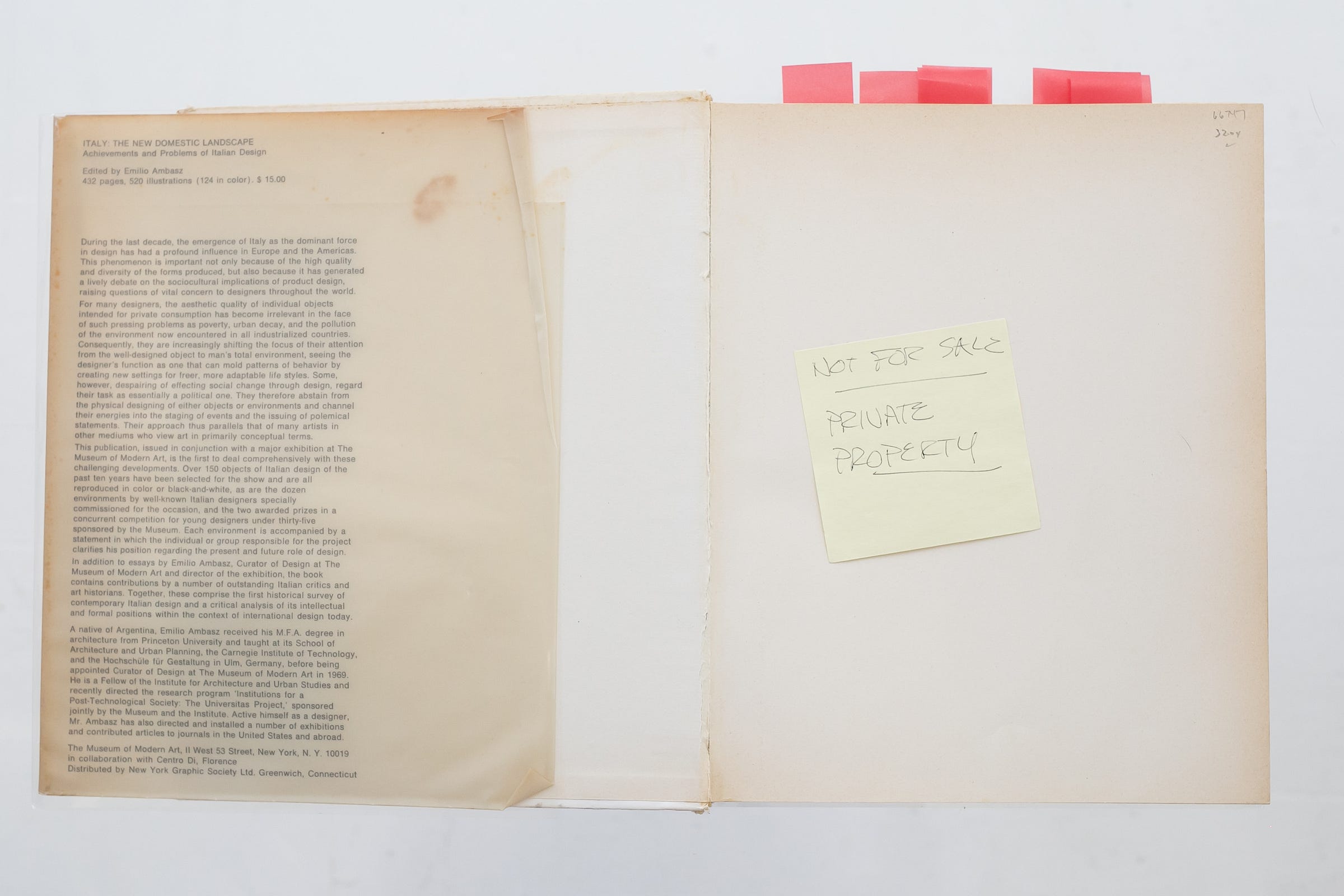

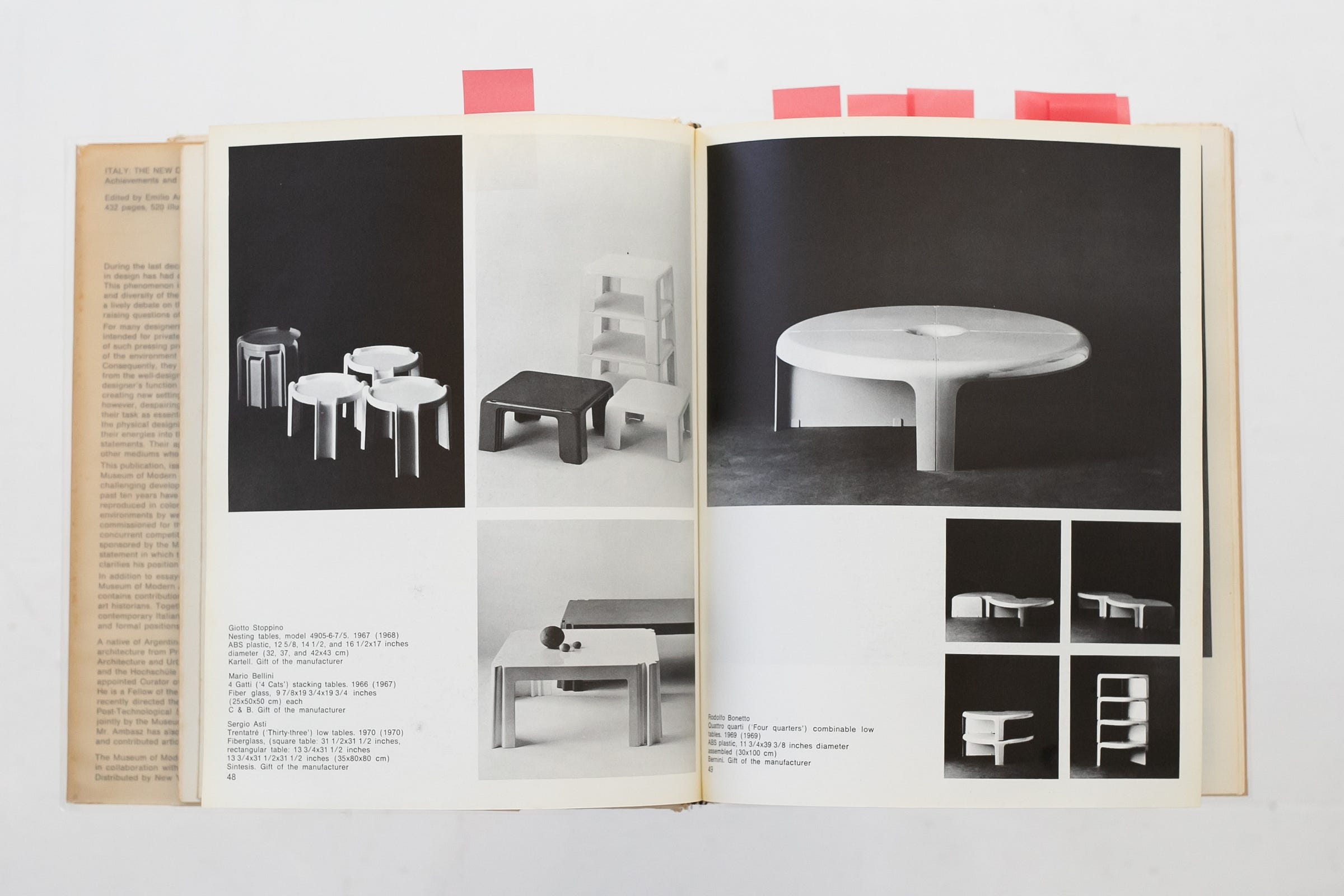

My desk was a long piece of white laminate wood balanced on two mismatching file cabinets, a stack of books on the right cabinet made up the height difference between the two to keep the desk level. One of these books was the exhibition catalogue for The Museum of Modern Art’s 1972 exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape. The dust jacket was yellowed with age. The book’s pages were tagged with red Post-its earmarking different chapters of interest to its former owner, who had likely left it in the apparent hurry to leave which I had not witnessed but was made aware of nonetheless due to the state of my surroundings. A note stuck to the book’s front endpaper read “NOT FOR SALE. PRIVATE PROPERTY”.

While almost all of the store merchandise was long gone, one of my colleagues spent the first few days of our tenancy hunting down whatever relics remained within the rubble of the Roman Empire. He recovered some hand-drafted architectural drawings of the building’s facade, a Burberry boys’ blazer that only required minor tailoring and is now a staple in my closet, one chunky Balenciaga track shoe, a scrapbook of polaroids cataloguing shoplifters during the department store’s heyday, and so, so many designer dust bags. Late nights at the office were spent with my colleagues plundering the bar in Fred’s in search of unopened bottles of liquor. Barneys as an institution had never meant anything to me personally—I never visited the department store while it was open, and certainly couldn’t afford to shop there—although I appreciated the fact that the building was a Peter Marino design, whom I had seen at many an art fair of mine (“Who’s the leather daddy?”).

The project at Barneys New York was unfortunately never realized, and by the fall I was left with only some photos on my camera roll and as many contemporary artifacts-turned-talismans as I could fit inside of a banker’s box. The exhibition catalogue for Italy: The New Domestic Landscape was one of my favorite spoils. I had given this book a narrative, and myself a bit of a savior complex—while beloved, its previous owner had unknowingly left it behind, hidden under the makeshift desk. It was my responsibility to ensure the catalogue was not forgotten this time, lest it be reduced to mere ephemera. Alas: once home, I nestled it within an aesthetic stack of publications on my entryway table with only a vague intention of ever touching it again, as is typically the fate of art books.

Intentions aside, and stuck at home one especially cold evening that winter, I went looking through my stacks for some reading material. On a whim, I picked up the book that I had swiped from my time at Barneys.

The 1972 MoMA exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape was curated by Argentinian architect (and then-Curator of Design at the museum) Emilio Ambasz. The show was the first major survey of modern Italian design, lauded by the museum as “one of the most ambitious design exhibitions ever undertaken by The Museum of Modern Art,”2 and, in hindsight, is still considered one of MoMA’s seminal exhibitions—looked to as the catalyst for popularizing modern Italian design ideas both in the US and internationally. Put another way, there have been exhibitions about this exhibition. By the early 1970s, Italy's rapid postwar transformation from a regionalized, agrarian society to a predominantly industrial one was just barely in the country's rearview. With Italy's modern era in its infancy, its meteoric rise within the intrinsically neoteric discipline of consumer-centric product design was notable and indicative of radical ideas and approaches. Ambasz speaks to this transitional moment in the catalogue’s introduction:

The emergence of Italy during the last decade as the dominant force in consumer-product design has influenced the work of every other European country and is now having its effect in the United States. The outcome of this burst of vitality among Italian designers is not simply a series of stylistic variations of product design. Of even greater significance is a growing awareness of design as an activity, whereby man creates artifacts to mediate between his hopes and aspirations, and the pressures and restrictions imposed upon him by nature and the manmade environment that his culture has created.3

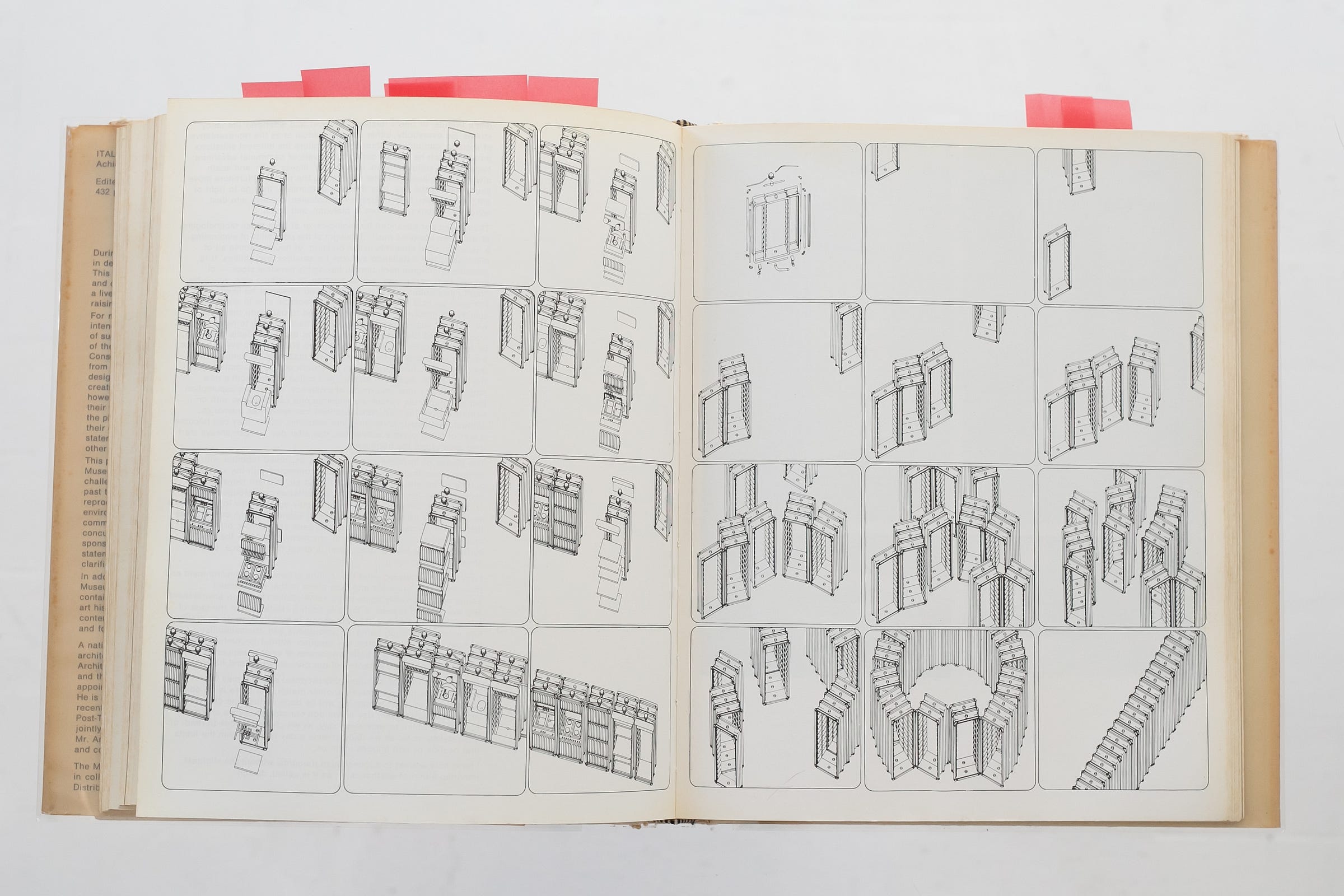

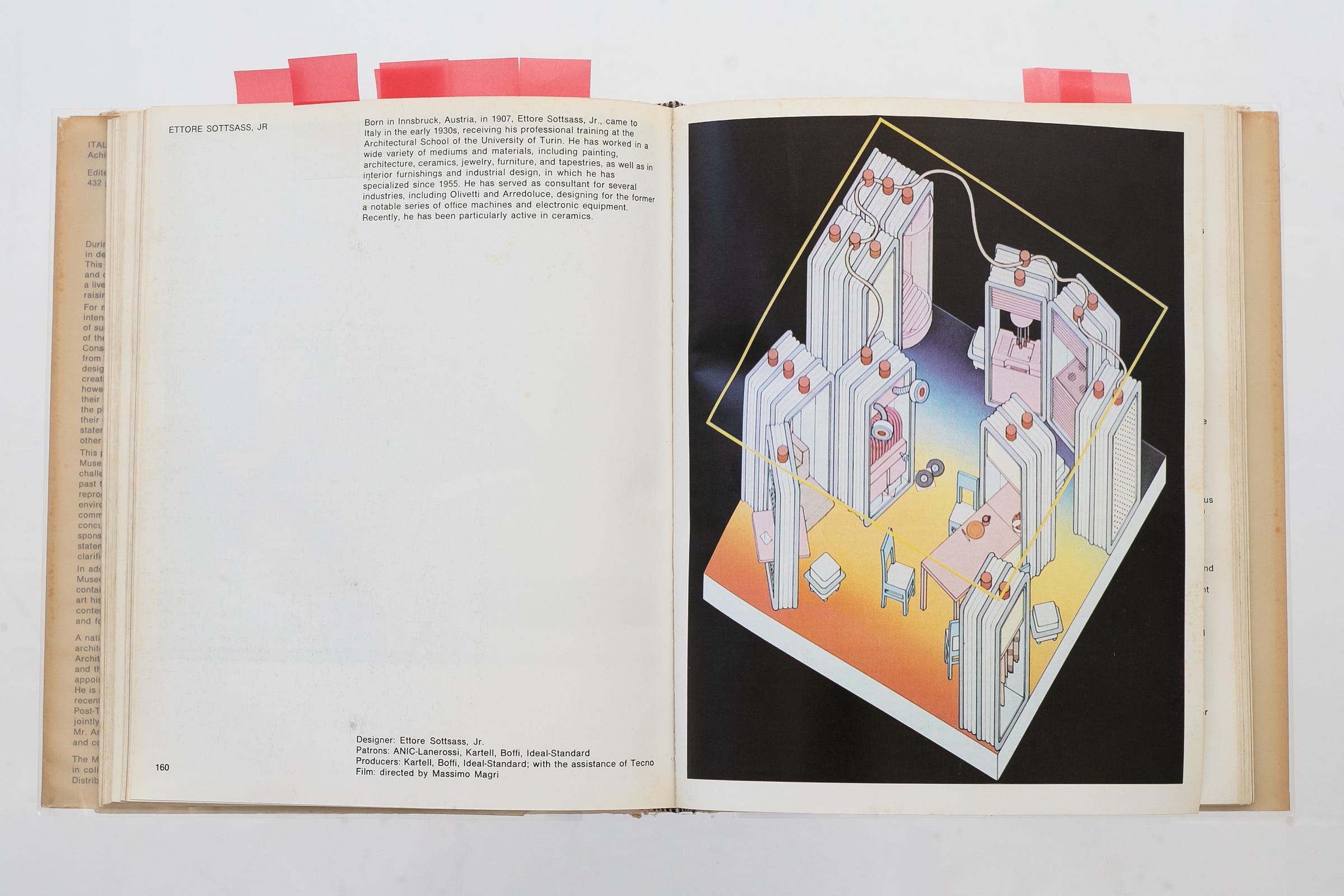

The show was organized into two modes of display. The first was a selection of 180 objects, each chosen for its unique design position and displayed in commanding wood-paneled columns throughout the museum’s outdoor sculpture garden. These objects functioned to provide the cultural context that informed the second: twelve experimental interior environments from leading and emerging figures in Italian design created specifically for the exhibition. The catalogue was similarly presented, with a section dedicated to object images followed by an in-depth look at each of the exhibition’s environments, accompanied by an artist statement from the designer or design studio.

In deciding what to read first, I figured one of the red page markers was as good of a starting place as any: I’m not one to start a TV series from the beginning and I prefer to listen to my music on shuffle. (I’m an agent of chaos.) I flipped through to a Post-it earmarking an environment conceptualized by Ettore Sottsass, Jr., aka “that mirror guy” or “the Memphis guy”, and settled in.

As an aside, and so my position is clear: I like the Ultrafragola mirror, even if it is a status selfie agent. It’s cute and yonic and the mirror's short run at the top of contemporary design listicles feels proportionate to its design merits within today's aesthetic sensibilities, beginning in earnest around 2019 during its reissue by manufacturer Poltronova, and waning sometime around the end of last year, due in part to the mirror’s formal similarities with Instagram's squiggly candle aesthetic that the internet has since deemed "avant basic".4 With dupes running upwards of $1K, the spray foam mirrors du jour could be considered the poor man's Ultrafragola. In a testament to how rapidly interior design tastes change these days, the author of a recent Architectural Digest article documenting the mirror's rise and fall notes her surprise upon spotting an Ultrafragola mirror during Emma Chamberlain's 2022 AD home tour with the singular refrain, "Still?"5

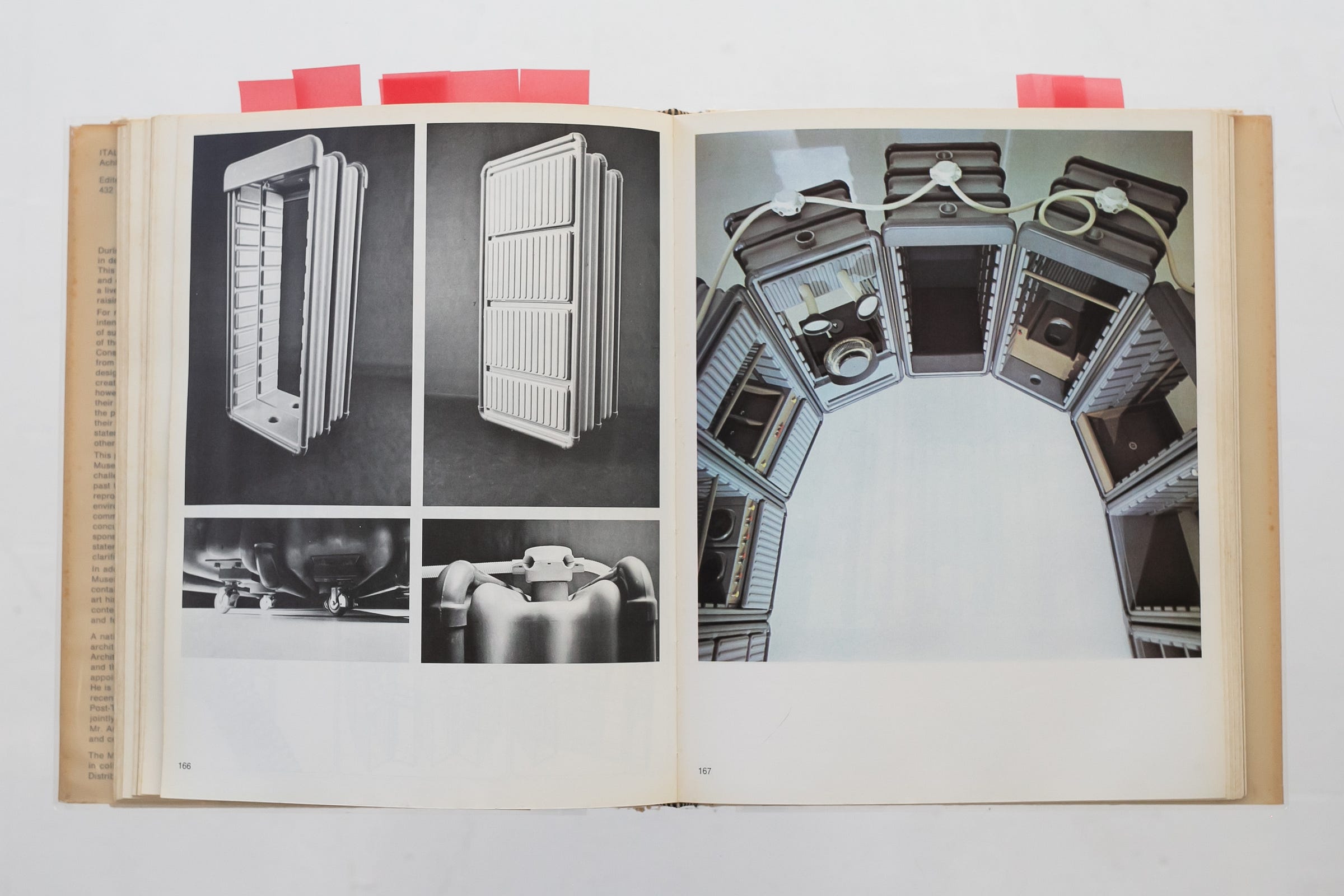

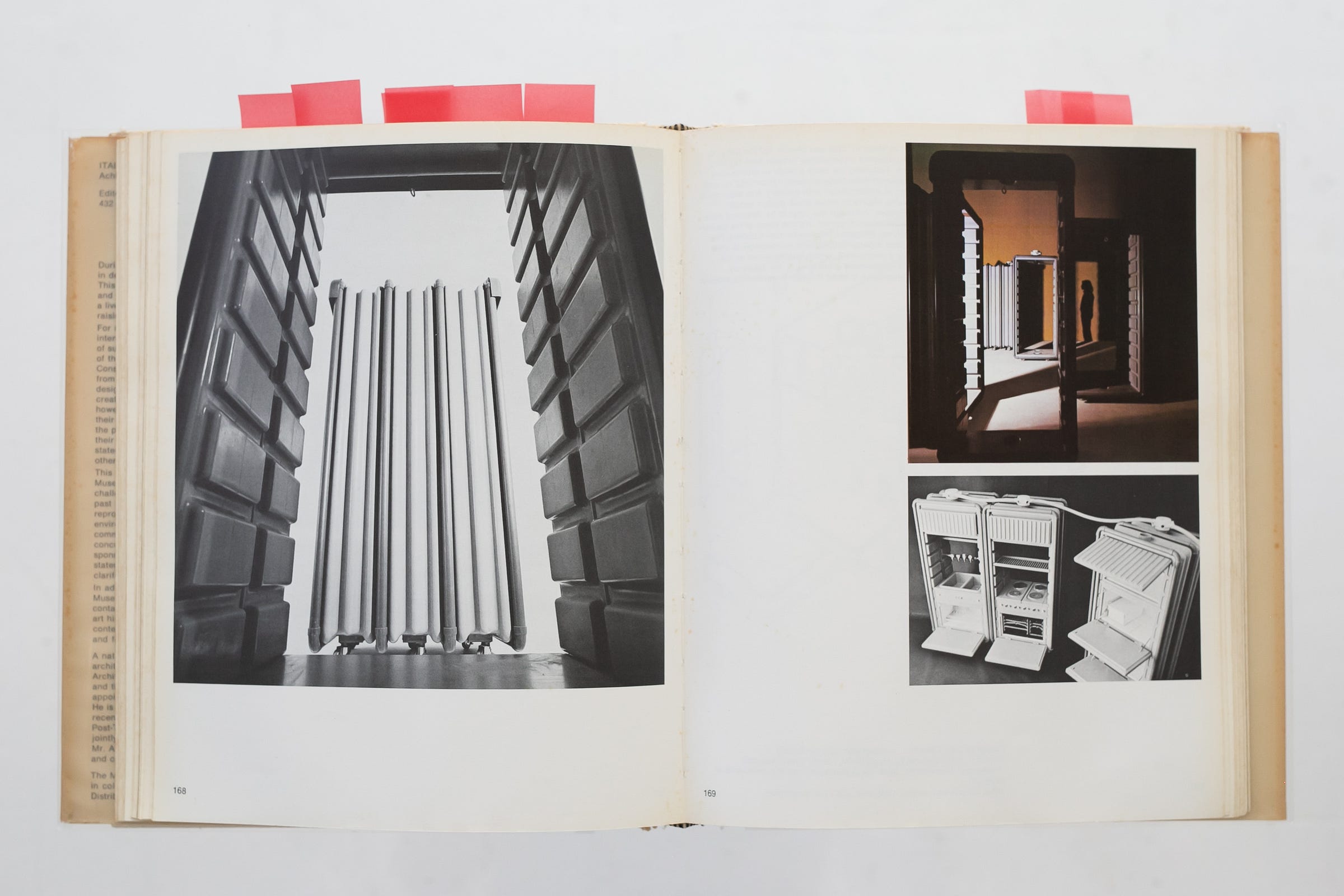

Sottsass was the founder of the influential Memphis Group, and as such I associate his oeuvre with bold colors, whimsical forms, and playful, irreverent adaptations of scale and material. I expected his contribution to the MoMA exhibition to similarly fall into this narrowly defined mode of creative output. Sottsass’s environment, however, was antithetical to the work that has defined his legacy. His proposed domestic landscape was austere and utilitarian, comprising of grey, ubiquitous plastic containers that could be both customized and mobilized to fit the various needs of an individual’s domiciliary life. In his words:

The form is not cute at all. It is a kind of orgy of the use of plastic, regarded as a material that allows an almost complete process of deconditioning from the interminable chain of psycho-erotic self indulgences about ‘possession’. I mean the possession of objects, I mean the pleasure of possession that seems to us precious, that seems to us precious because it is made out of precious material, it has a precious form, or perhaps because it was difficult to make, or may be fragile, etc.6

These containers were intended to quietly and optimally frame the ever-changing tableaux vivant of our daily lives. The desired psychological effect of Sottsass’s environment is reminiscent of the practice of mindfulness as we know it today, encouraging a soft awareness of our surroundings—noticing, without judgement. Through adding or removing a catalogue of modular, interchangeable household elements, such as a stovetop, a fridge, a record player, a toilet, a television, etc., one could adapt their environment as often as one pleased to match their evolving needs, tastes, and prerogatives. The containers were set on wheels, designed to be easily pushed by a child, and thus could also be repositioned as needed to facilitate daily activities or delineate between private and communal spaces.

The pieces of furniture move like beasts of the sea, they diminish or increase, they go right or left, up or down, they coalesce into colonies, dissolve into dust, solidify into rocks, or soften to plankton, and so on.7

To realize his vision of a home in flux, Sottsass felt it necessary to design housing infrastructure that could be easily and totally wielded by its occupant. Containers requiring electricity or water (or "heat, air, refuse, words, sounds, or anything else", as Sottsass postulates8) could be hooked up to a localized resource supply via overhead cabling, eliminating the need for installation systems to render services and utilities. In theory, this infrastructure could support resource sharing under a sharing economy framework. In giving the dweller absolute agency over their environment—through the structural and spatial makeup of their interior as well as the selection of their household needs and the resources required to power them—Sottsass aimed to release some of the rigidity our surroundings impart on us, providing the occupant with the freedom and tools to start each day with a "new awareness of existence"9.

But there is no doubt that, sooner or later, something will be done so that one can put on one’s own house every day as we don our clothes, as we choose a road along which to walk every day, as we choose a book to read, or a theater to go to; as we daily choose a day to live, within the limits that destiny or fate impose upon us.

I have only wished to suggest such thoughts, without the slightest intention either of aesthetics or, as it is called, design.10

For the exhibition, Sottsass chose to display what he considered “pre-prototypes”11 of his containers alongside a short film demonstrating how to use them. His containers were never manufactured nor conceptualized further, so the only visuals that exist were produced for this exhibition. Curious, I went searching for the exhibition film on the internet. Curiously, the video I was looking for had been uploaded to YouTube only 22 hours earlier and had two views. The same YouTuber had uploaded seven other environment films from the exhibition. A bit weirded out by the coincidence, I searched again to see if the video existed elsewhere on other sites or platforms, but no dice. I wouldn't have been able to find the exhibition film if I had sought it out the night prior. My first inclination was, “this has to mean something, right?”

In that moment I felt the same sense of exploration as I had during my brief stint at Barneys. The discovery felt ephemeral, so I started screen recording my phone in the event that this was a farce and the video would be taken down now that I had found it. In contrast to Sottsass's utilitarian design and staid artist statement-slash-manifesto, the exhibition film was dreamlike and perverse. A blonde model and her accompanying cast of characters demonstrate how to use Sottsass's compartments within what could hardly be considered a typical domestic landscape, set to snippets of Pink Floyd’s 1971 album Mettle. The film, which can only loosely be described as a product demonstration, is comprised almost entirely of non sequiturs: tears of blood, a mysterious man with exaggerated facial tics, some overt Communist symbolism, and maybe murder (I can’t tell).

While the ideas explored by Sottsass in his environment for Italy: The New Domestic Landscape are interesting enough, the real insights for me came from how I stumbled upon them: I had been one of a only few to step foot inside 660 Madison that summer, worked from an office which I had chosen at random, found an exhibition catalogue hidden under a desk, took it home in an attempt to hold onto what had become a fond transitory experience, picked it up almost a year later on a whim, flipped through it capriciously to find Sottsass’s environment, and finally searched online for its accompanying exhibition video, which had been uploaded mere hours before I went looking for it. Each step of the journey begot another. At the end of this wormhole was a work aiming to desensitize us to the “pleasure of possession”—in the midst of my desire to possess a book that I had found in the former Barneys New York flagship, once the great cathedral of consumerism of our time! Back to my gut feeling, “This is kinda sus. It has to mean something, right?”

For me, insights lead to more lines of inquiry. Speaking from my point of view as a 90s baby well adjusted to the unchecked horrors and absurdities of late-stage capitalism, what’s so bad about taking pleasure in possession?12 I imagine the looming consequences of consumerism weighed somewhat heavily on designers working at the forefront of product design in Italy during the 1970s, a time when the discipline's psychological impacts were just being considered amid the country's rapid industrialization and adoption of mass production. This might explain why Sottsass's approach is a human-centered one, designing an environment that subtly curbs our materialist tendencies while also prioritizing our personal agency. Perhaps this moment is similar to the current moral conundrum of A.I. hyper-acceleration: the technology precedes a full understanding of its implications, and the gap between the technology's capabilities and its yet-to-be-realized consequences continues to grow exponentially by the day. It’s hard not to experience existential dread when thinking about accelerated change, especially when our modern problems feel so cyclical. In these moments I think about the first few lines of Yeats’s poem “The Second Coming”:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

“And what rough beast, its hour come round at last, / Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?”13 The last line of this poem has lost a bit of its bite for me recently, maybe from beast fatigue: pandemics, natural disasters, economic collapse, political and social upheaval of the unprecedented variety, and so on. Paradigms are shifting so quickly that it's hard to keep up. Fifty years later, is the psycho-eroticism of possession that Sottsass designs against in his proposed domestic landscape merely experienced today as the dull, fleeting ache of satisfaction upon arriving home to a bunch of SSENSE packages? What is the beast that needs to be slain as it relates to materialism today, and can it be killed on behalf of our lived environment? Sottsass's interior aimed to prevent "memories [from] solidifying into emblems"14, instead favoring a fluid understanding of our past to permit us the freedom to start each day anew. But is there something to be said about the innate human urge to collect, especially to remember? Sure, every Klarna purchase of a checkerboard rug from Urban Outfitters in pursuit of the perfectly eclectic mix of "avant basic" home décor is another drop in the slow drain on society's collective will to live, but what does it mean when the act of possession is not directly tied to consumerism, such as keeping a love note written on a napkin, picking up a cool-looking stone during a walk, or stealing an exhibition catalogue from a derelict department store? This happens more on our phones now than ever: many of our contemporary artifacts are stored on our camera rolls, in our Apple Wallets, in iMessage. I feel the pang of self-indulgence that Sottsass speaks to when I screenshot a meme.

Maybe a more fruitful exercise would be to pose a different question: How to cope? We’re here now, living among these rough beasts of our own design, more are slouching toward Bethlehem as I type, and everyone’s apartment looks the same. I’m going to revisit Sottsass’s emphasis on self-agency as a possible response, as chaos often leaves us looking for something that we can control, and, in a cruel world bereft of Sottsass’s containers, in many cases our internal environment is the only thing that we can control. How can we find personal power at a time when self-expression has been commodified and the prevalence of Instagram therapy-speak has made it hard not to pathologize any selfish tendencies as shameful, toxic red flags? Internet culture has both created and perpetuated the idea of “Main Character Syndrome”, a modern affliction characterized by self-delusions of grandeur, a naive, exaggerated sense of self-importance at the expense of the autonomy of others, the NPCs of the world. I don’t want to film a TikTok dance in the middle of a crowded sidewalk, forcing everyone to walk around me, but I do want to live in a world of my own design, one where my actions have meaning and I’m the protagonist in my own story. Recognizing the serendipitous moments in our lives and acting accordingly is essential to exercising our personal power and, more radically, can be an act of self preservation. Maybe the psychological effects of this outlook are similar to wheeling around a container according to my whims. What if the only reason I was brought onto the Barneys project was so that I could write this post, so that you could read it? Synchronicity is a blessing, and should be acknowledged.

I’m not sure if these moments in life that feel perceptively full circle are infrequent (at least that’s how I experience them) or if they are more available to us and we just don’t take the time to follow the breadcrumbs or connect the dots.

Is it so wrong to think that something could exist just for me? Or as well, just for you?

While a “contemporary artifact” might sound like an oxymoron, I think the term is an accurate reflection of the pace in which we consume today’s material culture, and I use it throughout this essay.

The Museum of Modern Art. The Museum of Modern Art Press Release, May 26, 1972. Accessed March 14, 2023.

Emilio Ambasz, “Introduction” in Italy: The New Domestic Landscape ed. Emilio Ambasz. (Florence: Centro Di, 1972), 19.

Charlie Squire aka evil female recently wrote a fantastic post diving into this aesthetic, which they dub "Instagram Store Core".

Hayley J. Clark, “The Ultrafragola Mirror Has Been Duped to Death.” Architectural Digest, November 30, 2022. Accessed April 7, 2023.

Ettore Sottsass, Jr., Artist Statement in Italy: The New Domestic Landscape, ed. Emilio Ambasz. (Florence: Centro Di, 1972), 162.

Sottsass, Jr., Artist Statement, 163.

Sottsass, Jr., Artist Statement, 163.

Sottsass, Jr., Artist Statement, 163.

Sottsass, Jr., Artist Statement, 163.

Sottsass, Jr., Artist Statement, 163.

This is somewhat of a leading question. While I am only focusing on the psychological impacts of consumerism for this essay, any omission of its environmental, economic, and sociopolitical impacts, of which there are many, is not intended to diminish their importance.

William Butler Yeats, “The Second Coming,” in Michael Robartes and the Dancer. (Dundrum: The Cuala Press, 1920), 19.

Sottsass, Jr., Artist Statement, 163.

What an incredible essay... I am blown away by your writing! Thank you for tagging me so I was able to read it <3